Buildings matter. We spend the vast majority of our lives in them – whether that’s in our homes, when we go out, in the office or on the factory floor. Vast resources are spent making, powering and heating them, creating a huge carbon footprint. For humanity to win the fight against climate change, buildings and the way they’re made have to change dramatically.

BUILDING CONVERSATIONS

A series of short videos on some of the key aspects of the Building a more sustainable future report:

BUILDINGS HAVE A CRUCIAL

ROLE TO PLAY IN TACKLING

CLIMATE CHANGE

About half of all the resources extracted from the globe are used

for housing, construction and infrastructure. The most prevalent

materials used are concrete and steel, which are both very energy

intensive to produce using current techniques.

A CONCRETE FUTURE

CARBON-CURING CEMENT

After concrete is laid, the hydration process –called curing — typically lasts a month or so. As it cures, concrete absorbs some CO2. Several companies are working on tweaking the composition of cement in order to improve its CO2 absorption capability.

CEMENT ADDITIVES

Swiss chemicals company Sika is developing concrete mixtures that can reduce emissions by replacing up to 50% of clinker, a key ingredient in the production of cement that generates significant amounts of CO2.

CROSS – LAMINATED TIMBER (CLT)

This renewable material (planks of sawn lumber which are glued together in perpendicular layers) can be substituted for cement and concrete in certain contexts. The world’s tallest timber building, Mjostarnet in Brumunddal, Norway, uses CLT for stairwells, elevator shafts and balconies.

STEEL AND ITS ALTERNATIVES

The steel industry is another significant contributor to global CO2 emissions, just a tad above the concrete industry at 8% of the total. A key element of carbon emissions from steel is the use of metallurgical, or coking, coal.

Many major steel companies have plans to shift to zero-carbon steel through substituting ‘green’ hydrogen produced with renewable electricity for coking coal. While not yet cost-effective, it could be by 2030 to 2040 according to some estimates. Other methods of reducing emissions include improving the energy efficiency of existing steel plants and increasing the recycling of scrap steel.

BUILT TO LAST

One obvious way to slow the growth in demand for building materials, and related emissions, is to design buildings to last longer.

PLASTIC PIPES

These are much better for the environment than other traditional materials such as copper pipes. There are several reasons for this: they can be made with recycled plastic (which can itself be recycled), they are easier and cheaper to transport and they have a longer life.

MODULAR HOMES

Building houses in a factory allows greater precision, which makes them more energy efficient compared to homes built onsite using traditional methods. Materials are used more efficiently in factory production, with less waste generated, adding to the environmental benefit of modular versus traditional house building. And with labour and materials prices rising, there is also potential to lower costs.

RETROFITTING

But the reality is that existing building stock will still represent the majority of floor space in 2050, so meeting ‘net–zero’ targets for reducing global emissions will mean ‘retrofitting’ them to higher energy efficiency standards. This will be expensive, and is currently unaffordable, but some interesting developments are enabling renovations to be financed by future cost savings on energy and maintenance.

Figure 2: Global air conditioner stock (1990—2050) - Millions of units

Several factors have combined to drive growth in demand for air conditioning in developing countries. As workers move into cities, prosperity is rising, and so it the demand for cooling buildings: more comfortable temperatures mean more productive workers.

Source: IEA, The Future of Cooling

Please note: data beyond 2016 is projected

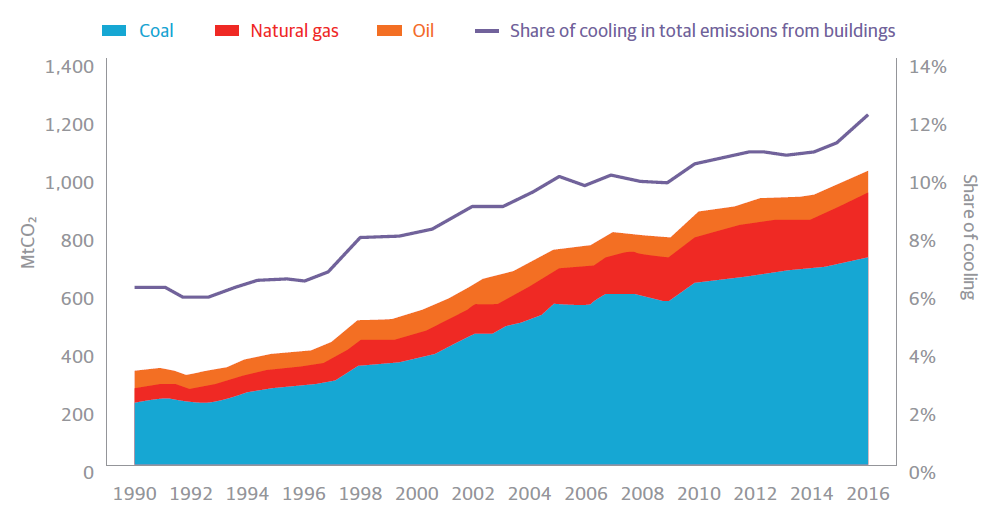

Figure 3: Cooling the world - Global CO2 emissions associated with space cooling energy use by source

Associated CO2 emissions could rise significantly because air conditioning units are primarily powered by coal–fired power stations in the countries using the most air conditioning.

Source: US Department of Commerce