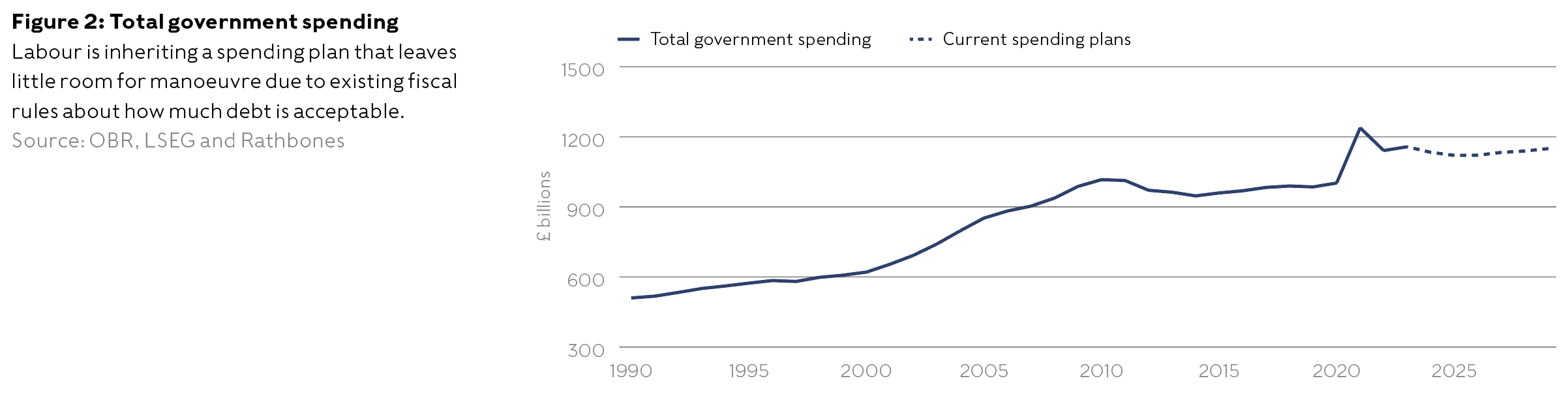

The spending restraint pencilled in by the new Chancellor almost certainly won’t happen, and she may find ways within the rules to borrow more. But investors understand the “fiscal fiction” in the current plans and are likely to tolerate some deviation from them.

Investment Insights Q3 2024: Bond markets can be forgiving (sometimes)

Article last updated 2 August 2024.

As Rachel Reeves moves into Number 11 Downing Street, where the Chancellor lives and works, she faces a fiscal conundrum. Her party’s manifesto pledged “no return to austerity”, yet she is inheriting plans containing significant spending cuts, and her room for manoeuvre is limited. She’s pledged not to increase the four taxes that raise most revenue, and to retain fiscal rules that limit her scope to borrow. Squaring this circle won’t be easy. However, the situation is better than the gloomier prognoses suggest, and we’re still happy holding UK government bonds.

How did we get here?

A little history helps to explain Reeves’ bind. Since the late 1990s, the UK government has set itself fiscal rules designed to keep borrowing within sensible limits. The precise form of these rules has changed many times, as they have been overtaken by events. But this time, the Starmer administration has pledged to retain the same key rule (the ‘fiscal mandate’) as its predecessor. This rule states that public debt must be projected (in the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) official forecasts) to fall relative to the size of the economy in five years. The spectre of the market turmoil that followed former Prime Minister Liz Truss’ ill-fated ‘mini budget’ has quelled any appetite for big changes to this framework any time soon.

Fiscal rules are great in theory, especially with memories of the ‘mini budget’ still fresh. However, in practice, they sometimes have significant unintended consequences. The debt rule has been no exception. It requires debt to be projected to fall relative to the size of the economy only in the fifth year of the forecast (and not over the period as a whole). This meant Reeves’ predecessor Jeremy Hunt could offer tax cuts ahead of the vote, while meeting the rule by pencilling in spending restraint after the election. This respected the letter of the law, but not the spirit of it, kicking the can down the road for the next government.

Adjusted for inflation, the plans that Labour is inheriting leave spending per person on public services unchanged over the next five years. Since spending on the NHS is highly likely to rise by much more than inflation, that implies sharp inflation-adjusted cuts elsewhere. Areas like justice and local government, which are already under severe strain, in principle face reductions of more than 2% a year. That’s before factoring in the desire to raise defence spending to 2.5% of GDP.

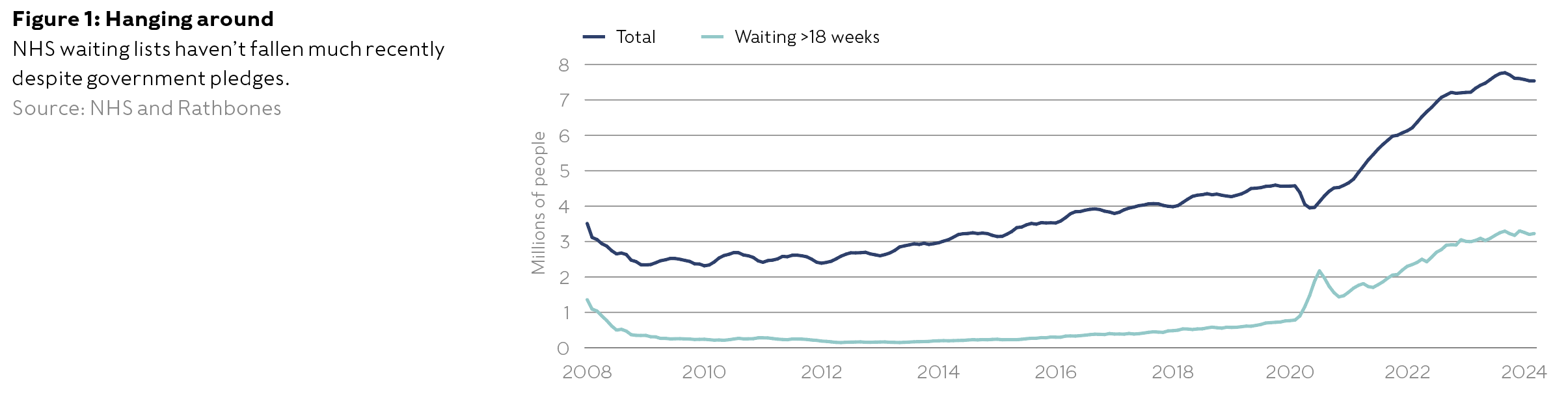

The Institute for Fiscal Studies describes these plans (inherited from the previous government) as “fiscal fiction” and argues they are not possible “while maintaining the current range and quality of public services”. The new government will be unable (even with a large majority) and unwilling to push through what would be Austerity 2.0. Doing so would do more harm than good, given signs that public services are still reeling from the impact of the pandemic on top of the original austerity programme. Hospital waiting times are far longer today than in the early 2010s (figure 1). Local government funding remains much lower now than in 2010 (after adjusting for inflation), contributing to problems including the growing number of car accidents caused by potholes. The justice system is under pressure too, with the backlog of Crown Court cases the longest on record.

Potential solutions

Therefore, Rachel Reeves needs to find a way to increase planned spending (figure 2). In doing so, she faces several constraints. Labour has consistently emphasised its commitment to fiscal rules and included them explicitly in its manifesto. This limits her ability to borrow to fund more spending. The party also promised in its manifesto not to raise the rates of income tax, national insurance, VAT and corporation tax — which together account for two-thirds of all government revenue.

The Chancellor hopes that stronger economic growth will lend her a hand. If the economy performs better than the OBR’s projections, all the trade-offs she faces become much easier. Economic expansion lifts revenues without the need to raise tax rates. With that in mind, Labour aims to support growth in three ways. First, by delivering the stability and predictability in policymaking which has been missing since the fallout of the 2016 EU referendum. Second, by directing more pension fund capital into UK companies. Third, by reform, especially of the planning system.

These goals are sensible enough. Investment in the UK has been held back by the post-2016 turmoil in domestic politics and in relations with our biggest trading partner, the EU. Pension funds invest much less than they could in UK firms, and the UK’s unusual planning system is clearly a barrier to growth. If delivered, these changes may indeed help increase the long-term rate of growth in the UK economy. Yet there are serious limits to this strategy when it comes to resolving the current fiscal bind.

One problem is that, even if all these proposals are enacted, any impact on growth may not be evident for years. In the coming quarters, blind luck will play a bigger role. As an open economy, the UK is highly exposed to global developments which are entirely out of the government’s hands. Whether the nascent economic recovery in the euro area flourishes or falters, for example, will probably make more difference in the short term than any of the domestic reforms floated. A prudent working assumption is that there will be no surprise boost to growth in the next year or so, meaning the government will have to resort to a combination of other strategies.

One such strategy is to increase taxes not explicitly frozen in the manifesto. Capital gains tax and council tax are possible targets. They’re the biggest ‘unfrozen’ revenue raisers. While Labour officials may have said that they have no plans to change them, that can change.

A more left field idea (with advocates all the way from the Financial Times to Nigel Farage) is to change the way the Bank of England pays interest on reserves to commercial banks, reducing the amount it pays out. This would be a de facto tax on banks. Reeves has sounded lukewarm when asked about this option, and Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey wasn’t enthusiastic either. But again, it can’t be ruled out entirely given the circumstances.

Another likely strategy is to test the flexibility of the fiscal rules. Ignoring them entirely, à la Kwasi Kwarteng, would be foolish and is not on the table. But other Chancellors have found ways to bend the rules to suit their objectives. Like Hunt, Reeves could maintain as little ‘headroom’ against the rules as possible. Like Gordon Brown, she could use partnerships with the private sector to exempt some investment from the public borrowing statistics. A further option this time around is to make a technical change to the way the Bank of England’s large holdings of government debt are treated in the fiscal rules. The independent Resolution Foundation estimates that this would allow the Chancellor an additional £16bn of space against the debt rule — a significant difference.

Will markets care?

Treating the fiscal rules in this way may sound too clever by half. But experience suggests that markets will be forgiving. The rules are now in their tenth iteration since 1997, so alterations of this kind are the norm, not an aberration. There’s a category difference between pushing the flexibility of the rules versus ignoring them entirely as Truss and Kwarteng did.

Markets are also likely to judge any extra borrowing based on its purpose. Borrowing to invest in the public services which underpin the economy is likely to be far more palatable than Truss-style unfunded tax cuts that today’s economic literature suggests were unlikely to boost growth. Numerous studies of the UK and its peers have found that slashing public services proved to be a false economy in the 2010s, failing to prevent debt from rising. By hurting investment and growth, it ultimately weakened the government’s ability to meet its financial obligations. Avoiding a re-run would be a good thing.

With all of that in mind, we remain comfortable holding UK government bonds in portfolios. Yes, the spending restraint currently pencilled in almost certainly won’t happen, and the Chancellor may find ways within the rules to borrow more than current plans imply. However, investors have long been aware of the “fiscal fiction” in these plans and are likely to tolerate some deviation from them. The global backdrop is also becoming more favourable for government bonds generally, with inflation back under control and interest rates starting to fall.