We think Labour is likely to be more of a help than a hindrance to the UK’s clean energy industry.

Investment Insights Q3 2024: Labour’s climate policy has implications for investors

Article last updated 19 August 2024.

It seemed, at times, that Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan— a pledge to invest £28 billion a year into greening the economy— was destined for death by a thousand cuts. In the end it limped, wounded, into the manifesto. But the taming of Labour’s initial ambition has prompted questions about the party’s devotion to the climate cause.

Now that Labour has secured a landslide victory in the general election, we explain what to expect from the new government on climate policy — and what this could mean for investors.

Leading the way

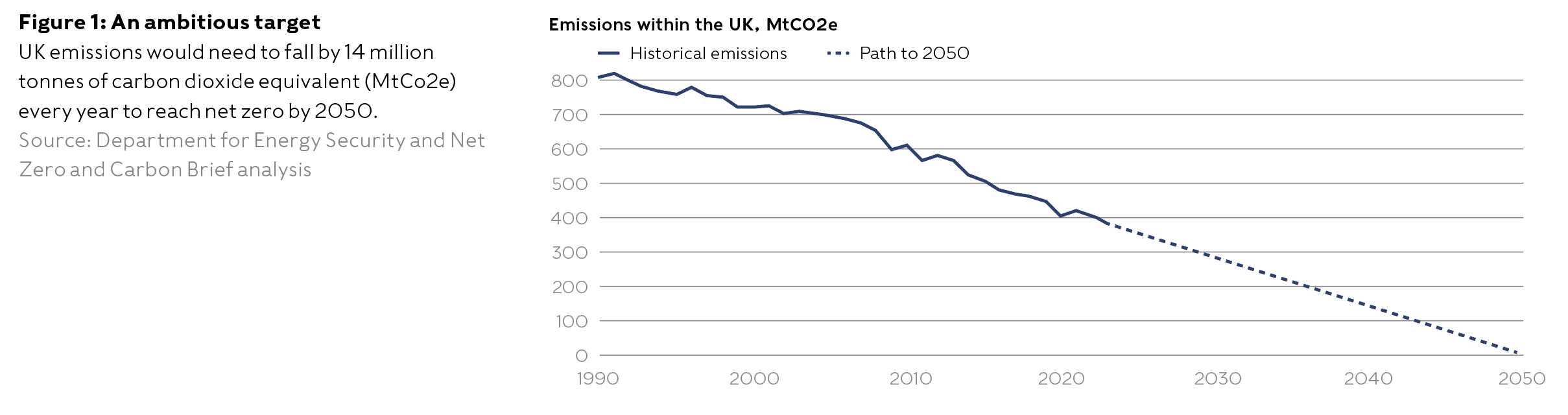

The Climate Change Act 2008 set an exacting target for the UK: reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050. It has since cut emissions faster than any other country in the Group of Seven (G7) bloc of large, advanced economies.

In 2019 UK premier Theresa May made Britain the first major economy to commit to net zero emissions by 2050. However, Boris Johnson’s ousting from office in 2022 marked a notable shift in government messaging, with Rishi Sunak U-turning on several key green policies in September 2023. Despite this, the net zero target has remained.

Before becoming Prime Minister, Keir Starmer said climate action was “at the heart of his economic vision for the UK”. Last year, Rachel Reeves, the then shadow Chancellor, declared that she wanted to become Britain’s “first green Chancellor”. But what can we really expect from the new government?

Stretching the purse strings

Labour has reduced its green investment plans from £28bn a year of additional spending — above what is already spent — to just under £5bn. That totals £23.7bn over the five-year parliamentary term. But we still think the new government will pursue a climate policy markedly different from the old government’s.

Central to the Green Prosperity Plan is an eye-catching mission to decarbonise the UK’s entire electricity grid by 2030. This means all — or virtually all — electricity coursing through the grid must come from renewable sources. That deadline is five years ahead of the 2035 date set by Johnson’s government. The UK has already made a great deal of progress here (figure 1).

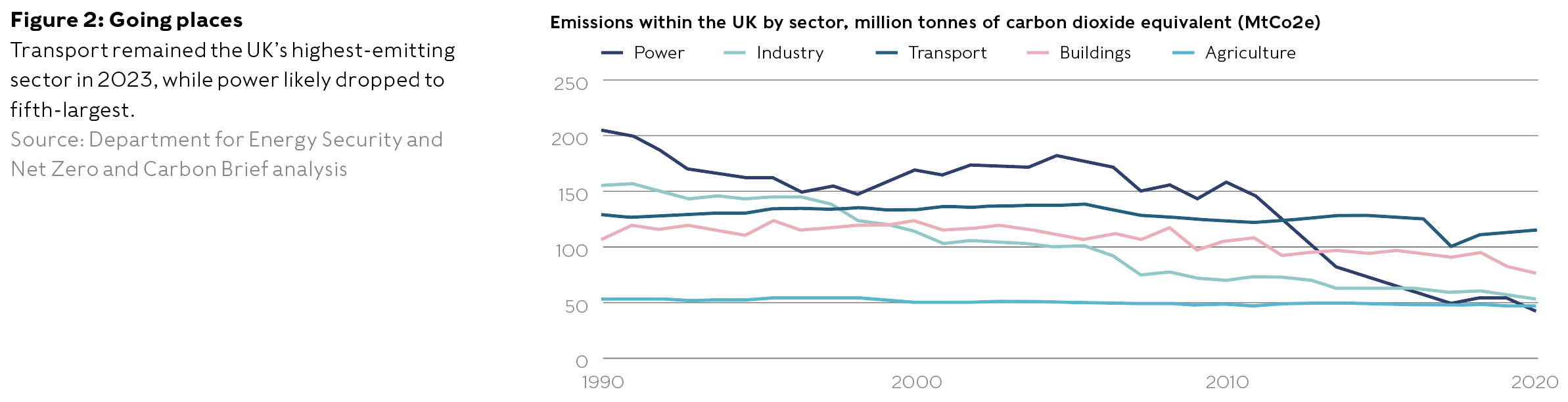

This is based on major updates to the grid, and a faster expansion in solar and wind generating capacity — both offshore and onshore — than under Conservative plans. Labour has also pledged to reinstate the 2030 ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars, though some analysts have raised doubts about whether this is feasible. Although the Conservatives had introduced the deadline, they later pushed the date back to 2035.

Switching on Great British Energy, a publicly-owned company in the mould of France’s EDF Energy, also promises to be an important pillar of Labour’s plans. GB Energy is, in partnership with the private sector, tasked to help fund the development of nascent — and therefore riskier — green technologies. Examples are floating offshore wind, green hydrogen and tidal power.

Labour has also promised to invest more in insulating homes. The party has set aside £6.6bn — less than an earlier number, but still double the previous government’s allocation — for its Warm Homes Plan over the course of its term.

Labour has also pledged to honour North Sea oil and gas licences granted by the previous government. But new oil and gas licenses, new coal plants and fracking — a controversial technique for extracting oil and gas from rock — are off the table. Labour says it will fund its plans through an increase in the windfall tax rate on ‘excess’ oil and gas profits, known as the Energy Profits Levy. It also wants to close “loopholes” in the Levy.

The vastly curtailed sum of green investment now planned has prompted analysts to question how far and fast the new government can go on net zero. Nevertheless, Starmer and Reeves, now in office as Chancellor, insist that through pragmatic policymaking and prudent spending, Labour can still deliver on its promises.

Pragmatism or poverty of ambition?

How do Labour’s net zero policies stack up against those of other parties? The short answer: Labour sits somewhere in the middle. We can expect the new government to go further on climate than its predecessor. But it’s unclear as yet quite by how much. Moreover, its policies and spending promises are considerably more restrained than the Liberal Democrats’ or the Green Party’s. Labour’s caution probably stems from a desire to shake off its image as a high-tax, high-spending party.

The Lib Dems had a manifesto pledge to achieve net zero emissions by 2045— five years sooner than promised by Labour. They also promised £8.4bn a year to tackle climate change and protect the environment. The Green Party said it wanted to achieve net zero carbon as soon as possible. It promised to fund its £40bn-a-year spending pledge to create a green economy through a multimillionaire wealth tax.

These policies increase pressure on the Starmer government not to renege further on its already diluted climate plans — not least because parties that want to green Britain faster could win disaffected Labour voters in the next general election. The green finance capital of the world

What does this all mean for investors in the UK?

In March’s Mais lecture to City grandees, Reeves saw government playing a bigger role in the UK economy in the future. When it comes to climate policy, this is borne out by its intentions for GB Energy. This has triggered concerns about the competitive landscape for private-sector utilities and renewables companies. Will they be less attractive investments?

We think Labour is likely to be more of a help than a hindrance to the UK’s clean energy industry. Its manifesto talked about GB Energy as a partner to existing energy companies in helping foster the growth of young and high-risk renewable technologies, as well as in scaling up more established ones such as wind power and solar. This is encapsulated in Labour’s undertaking to make the UK “the green finance capital of the world”.

This won’t transform the prospects of renewables companies — not least because the UK is already an attractive place for them, especially for offshore wind. However, if the new government puts real resources into GB Energy, this could lower the cost of capital for companies such as SSE that develop renewables.

In a recent podcast for Kepler Trust Intelligence, published by finance firm Kepler Partners, Stephen Lilley, fund manager at Greencoat UK Wind, described his conversations with Labour Party ministers as “all very sensible”. He did not see the new government as a source of disruption. Moreover, National Grid’s May decision to tap shareholders for nearly £7bn in a rights issue— which found willing backers — underscored its optimism about the post-election backdrop.

Playing our part

Back in 2021, Rathbones made a commitment to become net zero across its business operations and portfolios by 2050. Fighting climate change is important because it helps protect the value of our portfolios against the damage from climate change to companies’ earnings and balance sheets. We need to engage with businesses and the government to press them to go in the right direction on climate.

With this in mind, our stewardship team has outlined UK energy market reform as a priority area for our engagement. We believe it can create investment opportunities, in time lifting productivity by increasing access to cheap and efficient forms of energy. Meanwhile, it can help to guard against the financially material risks of volatile fossil fuel prices. Once the post-election dust has settled, we’ll join those pushing the new government to deliver on the wide-reaching overhaul of the UK’s transmission network grid set out in the 2023 Winser Review. We’ll also work with other investors to press the government not to forget its important ambition to deliver clean power across the UK by 2030. “Procrastination is the thief of time”, wrote the English poet Edward Young back in the eighteenth century. As we ponder how few years Britain has to reach net zero, we heartily endorse the sentiment.