The inflationary shocks caused by the pandemic and war in Ukraine are finally unwinding. But the welcome fading of these shocks doesn’t mean that we’re returning to an environment just like the one before they hit.

Investment Insights Q4 2023: Higher for longer

Article last updated 19 December 2023.

HIGHER FOR LONGER HAS IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS

The world has changed profoundly since the late 2010s, and the opportunities available to us as investors along with it. The strategies that serve us well today will look different to those that worked best in the unusual low-rate, low-volatility environment of the last decade.

The deluge

Just over a century ago, the world was also reeling from war in Europe and a pandemic, along with double-digit inflation. Contemporaries compared those events to a flood of Biblical proportions. Both Winston Churchill and wartime Prime Minister David Lloyd George called the period “the deluge”, an image also used by artists and poets of the time. By the early 1920s, the deluge was receding. Inflation had dropped sharply from double-digit rates as the acute turmoil subsided. The floodwaters also appear to be retreating today, with some of the damage done by the pandemic and war starting to heal.

For example, the once-in-a-generation chaos in global supply chains which followed the coronavirus pandemic has now largely abated. Last year’s lengthy delays at shipping hubs have disappeared, bottlenecks of critical components have dissipated, and firms have had time to rebuild their inventories. The outcome has been falling goods inflation, with further declines likely. Manufacturers around the world report that growth in their selling prices has slowed sharply.

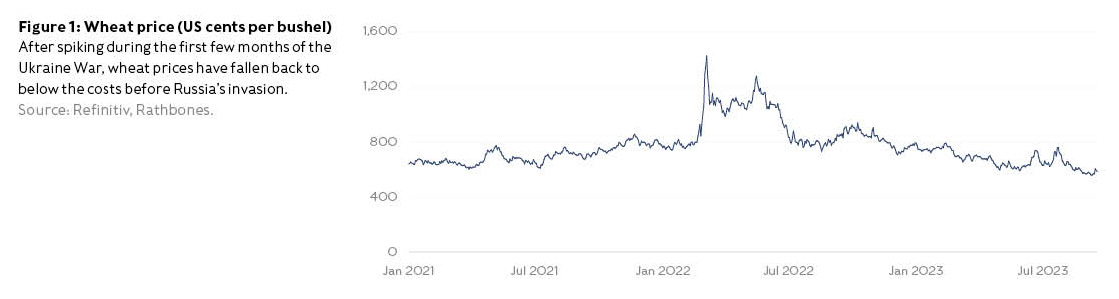

Although the war in Ukraine continues, a similar pattern is evident when it comes to its global impact. The prices of key commodities, like natural gas and wheat, jolted higher after the invasion. But they’ve since dropped to even lower levels than just before Russia attacked (figure 1). The world has adapted to the conflict in remarkable ways, reconfiguring trade routes or learning to live without Russian supply.

This too is already feeding through to lower inflation, helping to bring it from more than 11% last year to under 7% in the UK now. Again, there’s probably a lot more disinflation to come as the fading of this shock continues to filter through to consumer prices. UK food producers now report that the prior surge in their input prices is over.

We’re starting to see the first signs of that on supermarket shelves, and inflation there is likely to slow much further later this year. In the meantime, the statutory price cap on energy bills, which rocketed in 2022, is now declining. This alone should help to pull inflation down markedly later this year. Price pressures in the UK have not been tamed yet, but the outlook has improved considerably.

After the flood

Even as Churchill spoke about the deluge of his day subsiding, he argued that “violent and tremendous changes” had been left in its wake. Lloyd George, too, talked about “unheard-of changes”. The illusory stability of the Edwardian era gave way to a new regime of volatility in the interwar years.

Once again, there are parallels to the present day. Inflation may be abating — in the US it is already back in the low single digits — but other changes induced by pandemic and war will be with us for much longer. Both the challenges policymakers face and the tools they’re willing to deploy appear to have changed since the 2010s, suggesting that the economic backdrop in the coming decade will also look quite different.

Geopolitical rivalries have intensified, while awareness of the dangers that human interaction with the natural world can cause has increased. Governments are placing more emphasis on building resilience in supply chains, rather than maintaining efficiency (and minimising cost) as previously. And they’re increasingly willing to use long-neglected industrial policy to support this goal. Both the US and EU have passed major acts supporting domestic chip production and the green transition.

Through their experience in the pandemic, Western governments have also rediscovered their lost appetite for activist fiscal policy, in contrast to the budgetary consolidation of the 2010s. Consumers’ balance sheets have been strengthened by the huge fiscal interventions of the pandemic too. That’s another contrast to the years immediately after the global financial crisis, when households were trying to repair their damaged finances. In the round, the economic conditions which underpinned the demand-deficient regime of the last decade — when the monetary policy tools of central banks were compelled to do much of the heavy lifting — have fundamentally altered.

The new old normal

The full implications of these changes will take years to become clear. But we are confident about a couple of points. First, interest rates will stay higher on average than their rock-bottom rates in the 2010s, even as the recent burst of inflation continues to fade. The conditions that kept monetary policy ultra-loose for a decade have changed. Rates should fall from current levels at some stage, but not get mired near zero again. Second, volatility — in inflation, interest rates and economic performance generally — will be greater than it was during that decade. That reflects a combination of things, including the new policy environment plus the risk of greater geopolitical and climate-related shocks.

In some ways, these changes shouldn’t be at all surprising. The 2010s were unusual with the lowest interest rates in centuries of recorded history (from the 1600s in the UK), and the second-lowest volatility in inflation (going back to the 1200s). The ‘new normal’ after the pandemic and war in Ukraine might look more like the ‘old normal’ which preceded the financial crisis, with historians instead remembering the 2010s as the anomaly.

Adapting to a new regime

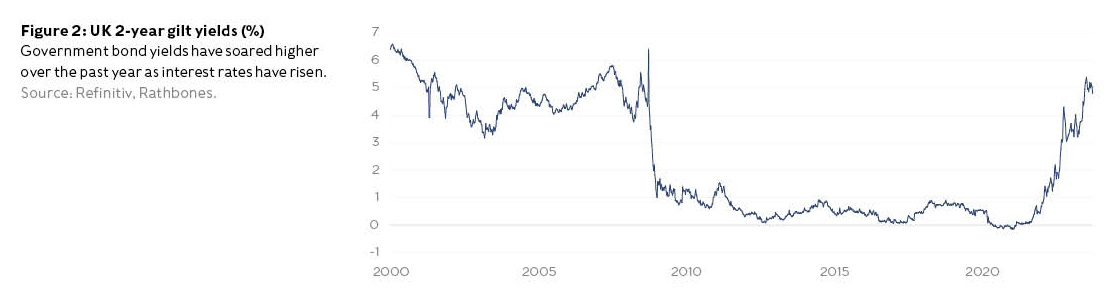

From an investor’s perspective, this regime change creates a need to adapt, but also presents opportunities. This is particularly evident in fixed income, where markets have moved in anticipation of this new environment. Higher rates mean higher yields available from fixed income assets with little or no risk of default (since those yields tend to be highly sensitive to expectations for interest rates). For example, UK government bonds (gilts) with a maturity of two years offered a yield well below 0.5% just two years ago, and 0.6% on average through the 2010s. Today, the yield is nearly 5% (figure 2). When we work out our long-term projections for returns from various asset classes, fixed income shows up more favourably than just a couple of years ago. It’s likely to comprise a larger part of our portfolios over the next few years, given the more attractive entry point.

Higher volatility arguably also creates opportunities for careful active management in fixed income over the ups and downs of the economic cycle. From that point of view, gilts have recently become more attractive than they have been for a long time.

The Bank of England appears to be at the end of its cycle of raising rates. While a return to near-zero isn’t on the cards, we think it will cut rates in 2024. The previous surge is starting to affect the economy, with inflation falling and the latest business surveys pointing to activity contracting. Although wages have been growing strongly recently, the broader evidence of loosening in the labour market suggests that will not last. Meanwhile, house prices are already falling, as we discuss in the article on page 8, and consumers tend to turn cautious when that happens. In the past, interest rates have nearly always fallen in the year after house prices began to decline too. This all adds to the tactical appeal of gilts, which in past cycles have performed strongly ahead of the start of rate cuts.