Mind the gap

UK CEO pay lags behind US peers - this article explores the reasons, risks of a brain drain, and how Rathbones approaches executive pay as responsible investors.

Article last updated 24 July 2025.

The heads of UK companies must be scratching their heads.

If they read the British newspapers, they’ll wince at complaints that they’re paid far too much. The High Pay Centre, a campaign group, said in August 2024 CEO pay at FTSE 100 companies had increased to a record high, with the average chief executive paid 120 times more than the average full-time worker at their own company.

If anything, public scrutiny of their compensation is intensifying, with the growth of initiatives such as the Fair Reward Framework. This is a forthcoming collaboration between the High Pay Centre and UK investors to monitor the earnings of both CEOs and the workforces they’re in charge of.

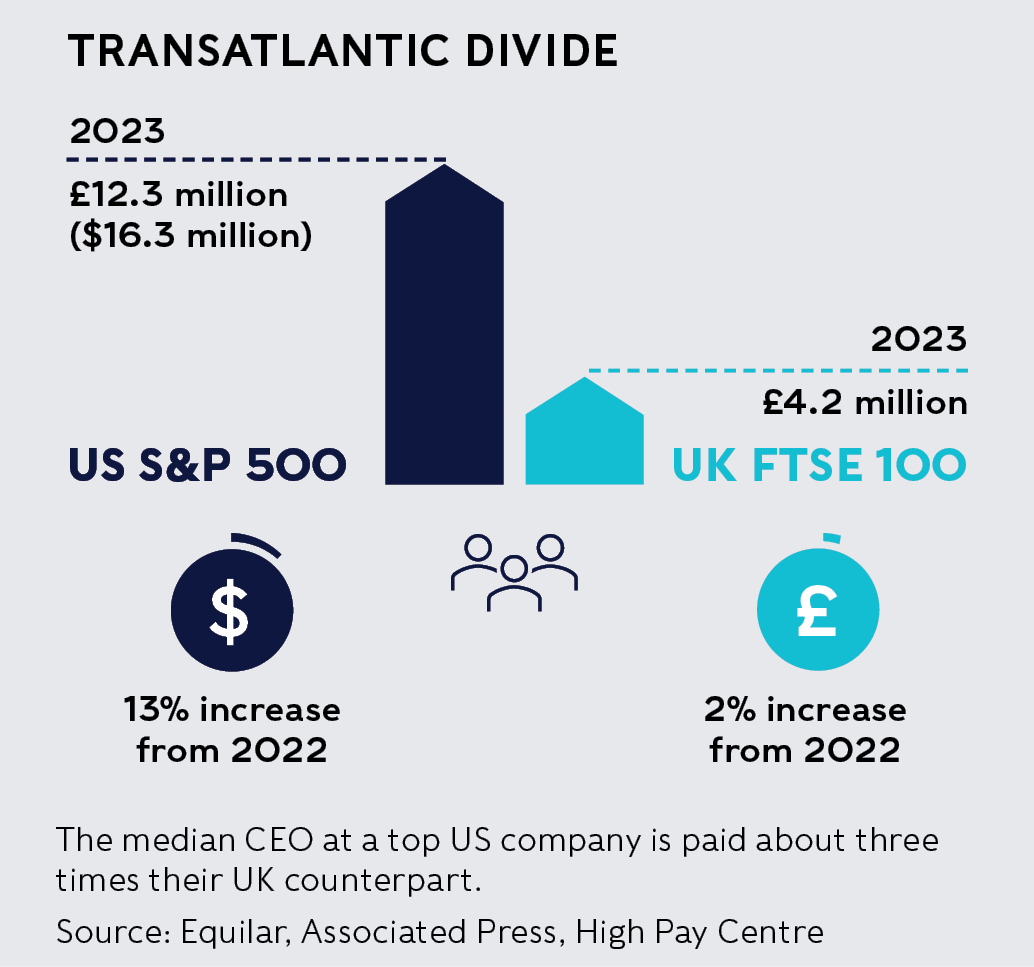

If CEOs look across the Atlantic, though, they see that the gap between executive pay in the UK and US is even wider than before.

This has prompted fears in some British boardrooms of a managerial ‘brain drain’ should top talent seek more generous packages abroad. There have even been worries that this growing executive pay gap could undermine the health of UK capital markets by sparking an exodus of companies from the London Stock Exchange (LSE) to greener (in other words, less heavily regulated) pastures in the New World.

A more cynical way of looking at high executive pay is to see it as a reward simply for being a CEO – the ‘gravy train’ theory – rather than for being a good CEO who might develop itchy feet if they’re not paid enough.

Are UK executives really short-changed?

In 2022 the CEO of UK-listed consumer goods business Reckitt Benckiser departed for a higher-paying job in the US. In March 2024, the head of UK industrial conglomerate Smiths Group did the same. Large UK companies are responding to this potential transatlantic migration by trying to pay their CEOs more – but this has courted controversy. This year, FTSE 100 companies such as pharmaceuticals business AstraZeneca, medical device maker Smith & Nephew and London Stock Exchange Group have faced resistance from shareholders asked to approve increases to CEO compensation closer to what US-listed peers are offering.

Partly in response to such resistance to top management pay, some company boards and investors are now arguing that the UK is guilty of an overly restrictive approach to corporate governance, imposed by regulators, shareholders and the specialist firms that advise them on voting. Critics say this has stifled the ability of boards’ remuneration committees to pay salaries competitive enough to keep talent on the right side (in both senses of the word) of the Atlantic. But is that fair?

Size isn’t everything

Schroders, a UK investment company, has looked at the pay packets of 2,353 CEOs at 1,980 companies of various sizes across a range of different cities in the US and UK. It calculates that American executives earn roughly five times as much as British bosses.

A common explanation is that disparities in pay reflect disparities in size. Looking at the largest businesses, the average company in the S&P 500 index of the biggest listed US businesses is about 4 times the size (in market capitalisation) of the average FTSE 100 company. Given this, it makes sense to pay top business leaders in the US more, since they run larger business empires.

However, the Schroders study also observed that after adjusting for company size, CEOs in the US still take home about twice as much as their UK peers. The pay gap was most acute at small and mid-sized businesses. On the one hand, Tom Gosling, executive fellow in finance at London Business School, cautions that the “2x or more difference in pay levels… is probably a bit overstated.” But even by his estimate, leaders of British businesses earn less than their peers across the pond, when taking company size into account. His analysis finds that after allowing for size, US CEOs are paid about 50% more.

Corporate governance: counterintuitive consequences

Such conclusions even add to worries that in the long term, pay could increase the impetus for listed UK companies to follow in the footsteps of a handful of high-profile businesses that have delisted from the UK market and relist on the New York Stock Exchange. These departing companies are in areas as diverse as building materials (CRH), plumbing supplies (Ferguson) and betting (Flutter Entertainment), though they do have something in common: the US is their biggest market.

This has prompted a search for solutions. In 2022, LSE CEO Julia Hoggett led a group of City executives in forming the Capital Markets Industry Taskforce. Its exalted goal was an overhaul of UK capital markets. High on the list of the taskforce’s reform agenda is a review of what it regards as “bureaucratic” corporate governance rules. It says these are making British companies reluctant to hand out competitive pay packages for top executives.

The UK’s approach towards corporate governance has clearly been more robust compared to the US’. In 1992, following a spate of corporate scandals involving names such as Polly Peck and the Mirror Group, the UK became the world’s first country formally to adopt a Corporate Governance Code. Many countries have followed suit.¹ The US is now the only major developed market that lacks one.

The US’ comparatively laissez-faire approach towards corporate governance is also reflected in differences in how executive pay is regulated. Shareholders of US companies are given demonstrably weaker rights than in Britain. Part-owners of businesses listed on the main UK market must be given a binding vote at least once every three years on how much a company proposes paying its executives. This is known as a ‘Say on Pay’ resolution. In contrast, while investors in US businesses are given a Say on Pay, such votes are merely advisory.

One might expect that the power shareholders in UK companies are given to reject rather than merely complain about executive pay should rein it in. But Bobby Reddy, a law professor at the University of Cambridge, is sceptical. Comparing the regulations in the US and UK, he concludes that “it is not axiomatic that the binding vote has resulted in lower executive pay in the UK.” In fact, he adds: “Causation is elusive to establish.”

Some people think such votes may, counterintuitively, have boosted executive pay rather than reining it in on both sides of the pond. That’s because boards now have to reveal executive compensation so that shareholders can vote on it. This means senior executives can spot who’s paid more than them and use this as ammunition to ask for more.

If corporate governance can’t explain the gulf between UK and US pay, and size can only partly explain it, what is the explanation? Reddy argues that in a world where pay packages are increasingly tied to share price performance, “executive pay may be higher in the US simply because the market has performed better.” He also suggests that cultural differences may have played a role too: American society is more accepting of higher pay.

Is there a brain drain?

Earlier on, we gave the brain drain examples of Reckitt Benckiser and Smiths Group. But it is, actually, very rare for an executive in what are known as the ‘C-Suite’ of top managers – chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and so on – to relocate from a FTSE 100 firm to a US rival. Moreover, in both cases, the departing CEOs were from among the very small number of FTSE heads who are American citizens. This is relevant because past research by Boardroom Insiders, an information company, has found that only 12% of CEOs at Fortune 500 companies (the 500 biggest US companies by revenue) were born outside America. And nine in ten of these had either emigrated to the country when young, been to a US college, or worked their way up through the international divisions of the company they eventually went on to lead.

By contrast, in more recent research headhunter Heidrick & Struggles finds that 42% of the heads of top UK companies aren’t British – roughly four times its equivalent number for top US companies. In other words, it’s not the US market that’s sucking in so many foreign CEOs, at least in relative terms – it’s the UK.

But if CEO pay is higher in the US, why don’t British CEOs follow the example of P.G. Wodehouse, Cary Grant and John Lennon by leaving en masse for America? One answer is that human motivation is complex. Some studies into what makes CEOs tick have concluded that the opportunity to do challenging and engaging work, which generates prestige, respect and admiration, is often a greater incentive than money.² We believe fears are overblown of a heavy migration of CEO talent and even entire companies from the UK because of executive pay.

A case of case by case

What does this mean for Rathbones?

When considering how much CEOs should be paid, we think it’s important to remember that they’re ultimately paid out of shareholder funds – the assets of a company that belong to shareholders, after subtracting liabilities.

We’re happy if shareholder funds are used to reward strong performance, which benefits the clients whose money we invest - and we’re open-minded about how this is structured. We’re also happy if shareholder funds are used to keep a talented CEO from defecting to another company. But the reasoning has to be rigorous – every million pounds more a CEO is paid is a million pounds less to allocate to something else, such as investing in machinery, marketing or innovation.

In other words, some pay packages merit a wince – but others don’t.

¹ From the CFA ‘Certificate in ESG Investing’, 2021, p. 198:

Polly Peck (1990/1) – Polly Peck was a textile and trading business that grew so rapidly in the 1980s that it joined the FTSE 100 in 1989. A prolific dealmaker, it later emerged that much of its apparent profit arose from the high inflation and associated high interest rates in Turkish Cyprus, where many of its operations were. CEO Asil Nadir fled to North Cyprus in 1993, returning to face trial in 2010. In 2012, he was found guilty of ten charges of theft.

² For example, www.vlerick.com/en/insights/salaris-minst-belangrijke-drijfveer-ceo/