The US Federal Reserve rows back on the potential for interest rate cuts even as inflation improves. Meanwhile, the French election also reverberates through bond markets.

Review of the week: Getting ahead of the Fed

Article last updated 17 June 2024.

QUICK TAKE:

Instead of staying flat at 3.4%, US inflation dropped to 3.3% in May

Major 10-year government bond yields dropped roughly 20 basis points last week

UK political manifestos create as many questions as answers

Major nations’ government bond yields dropped substantially last week as American inflation fell slightly. US CPI inflation, which is the measure most easily comparable to inflation rates around the world, dropped from 3.4% in April to 3.3% in May. It had been forecast to remain the same.

Decelerations in price rises for food, rent and transportation were the main drivers, along with outright falls in the cost of new and used vehicles. Petrol prices were higher than expected, offsetting some of the improvements. Core inflation, which removes volatile energy and food prices, dropped from 3.6% to 3.4%. That’s a noticeable and welcome fall in what has been a tremendously stubborn measure.

When the inflation report is compared with the previous month, there are more signs that the latest bout of inflation may be starting to ebb. While inflation in core services was steady at 5.3% year-on-year, the monthly rate was the lowest since September 2021. Excluding rent – which was more persistent, yet reliable leading indicators show should slow in the months ahead – core services prices actually fell slightly on the month. That's even true when we exclude airfares, which are volatile and fell sharply in May.

Government bond yields in the US, Europe and the UK dropped roughly 20 basis points (bps) over the week – sizeable moves. Bond investors see this as a herald for the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) long-awaited interest rate cuts. However, there are a couple of reasons why such a big move seems a little premature.

Firstly, this is one data point. We’ve been here before! Many times! We too think inflation should continue to melt away, yet how long this will take is impossible to determine with a high degree of certainty. As we’ve noted a few times, services (which includes businesses like cafes, cinemas, garages and accounting firms) are the mainstay of a developed nation’s economy. Most of these companies tend to be labour-intensive, so there’s a relationship there with wages. A slowdown in services inflation depends on slowing wage growth, which actually quickened in May. An unambiguous deceleration in services inflation will no doubt be a prerequisite for the Fed to start cutting rates.

Secondly, America goes to the polls in November. The campaign is in full swing and it's about as uncivil as you would expect. Claims of ‘lawfare’ (using the courts to fight your political opponents) and inherent biases within both the law courts and parts of the civil service are being asserted on both sides. To show its independence from politics, the Fed will be reluctant to do anything that could be construed as helping one side over the other unless it is absolutely vital. Say, if a shock sends the US economy into a recession and unemployment starts to jump. Otherwise, it seems most likely that it will wait till after the vote on 5 November before it makes any changes to rates (conveniently, its November meeting is held on the 6th and 7th).

Perhaps because of these two dynamics, at its meeting last week the Fed itself poured a bit of cold water on the idea that it will soon cut rates. The Fed’s monetary policy committee had sight of the May CPI report for its discussion. While Fed Chair Jay Powell described it as “encouraging”, he also said that the inflation report “comes after several reports that were not so encouraging”.

The Fed is more interested in PCE core inflation anyhow, which is a different measure that’s less comparable with global inflation rates. The Fed now expects core PCE to be 2.8% in the fourth quarter, up markedly from the 2.6% forecast made three months back. Now, Powell did downplay these changes as conservatively high yet, however you cut it, inflation is moving in the wrong direction. Meanwhile, the committee’s expectation for where rates would be in Q4 was 5.1%, which implies roughly one and a half 25bps cuts. Three months ago, they were predicting three and a half cuts.

Taking to the streets

Disappointment about the Fed’s lessened forecasts for rate cuts and higher forecasts for inflation was perhaps blunted by news on the other side of the Atlantic. US bonds had sold off in the wake of the Fed’s revelations, sending yields higher, yet they quickly dropped back as the week progressed. Was that because of increasing concerns about the snap French election?

French President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to dissolve the legislature after a poor showing in the European Union elections has been called a gamble. There are two theories about what exactly his plan is, however. The first is the short game: that Macron believes the French people vote for parties of the far-right and far-left in the EU Parliament as a protest vote, yet that they are reluctant to give them power nationally. The second theory is the long game: that Macron fully expects the far-right to take power in the coming vote – likely through ‘cohabitation’, where Macron remains President (head of state) but the Prime Minister (who controls the government) comes from a different party – but that they will botch it and be punished at the next election.

Whatever the true plan, it’s risky. France is in a pickle, fiscally speaking. It has been for a while and it’s gotten much worse since the pandemic. France owes a lot and is spending too much. But any time Macron’s government has tried to address this largesse, the people raise all hell, shutting roads, burning tyres, striking, the standard playbook. If France elects a hard-left or hard-right government, its policies are likely to only make this situation worse, whether by increasing spending, restricting immigration and trade, tax cuts, or all the above.

On 31 May, credit rating agency S&P downgraded France to AA-. The nation is spending more than it receives in taxes to the tune of 5.5% of its GDP last year. S&P had forecast that ‘deficit’ to be 4.9%. It doesn’t expect much improvement either, increasing its deficit forecast for the next three years to 4.6% from 3.9%. Remember, the EU’s fiscal rules state that a country’s deficit should be under 3% of GDP. Those rules also say EU members should be reducing their debt levels if they’re above 60% of GDP. France’s current debt to GDP ratio is 110% and S&P expects it to increase over the next three years. Now, the EU is renowned for leaving lots of wiggle room for its members – particularly the big important ones like France, Germany and Italy. Yet this is an unenviable prognosis even before more radical parties, which often increase deficits, get involved. This situation has spooked investors, with large flows into ‘safer’ assets, such as German and American government bonds. Although, there’s a touch of irony there, given US fiscal responsibility has been very lax lately as well! (Although, a country, like the US, which is in control of its own currency is less likely to need to default, especially if it imports relatively little and if inflation is under control.)

As for the election story in the UK, it’s been pretty muted by comparison. Labour remains the odds-on favourite to form a government. Labour, the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens all released their manifestos, with barely a murmur felt in markets.

|

Focusing on the two main parties, there wasn’t much to get anyone’s blood racing. The Conservatives announced £17 billion of cuts to National Insurance, mostly aimed at the self-employed. These are apparently “fully costed” and would come from cutting the welfare budget and cracking down on tax avoidance. The latter, especially, is a magic money tree for politicians – Labour is proposing to shake it too. If the tax avoidance was so easy to shut down, why hasn’t it already happened? As for Labour, the main issue of note was that its manifesto didn’t rule out hiking capital gains taxes in coming years if it makes it into Number 10. The rest of the document has mostly been heavily trailed by the leadership.

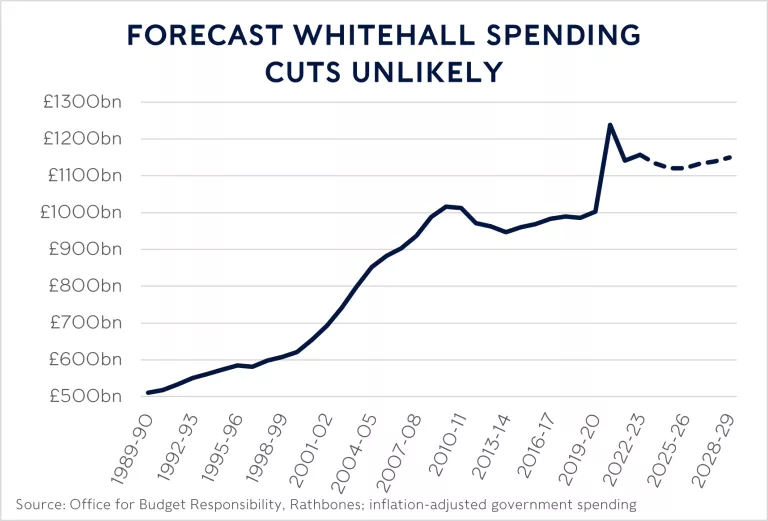

Regardless of who makes it into Downing Street, there remain serious questions over how any policy agendas will be paid for while abiding by the fiscal rules and common policies currently in place. For example, unprotected public services face cuts of between 1.9% and 3.5% a year (roughly £10-£20bn by 2028-29) according to forecasts in the March Budget, yet they are widely understood to be unfeasible.

If you have any questions or comments, or if there’s anything you would like to see covered here, please get in touch by emailing review@rathbones.com. We’d love to hear from you.